Source:

- Archive.org: BYTE Magazine 03-1984

- Direct download from WoM:

MULE_Review_BYTE_Magazine_1984-03.pdf (5.9 MiB, 531 hits)

MULE_Review_BYTE_Magazine_1984-03.pdf (5.9 MiB, 531 hits)

M.U.L.E.

Beneath its clever packaging lies a fascinating economic simulation

by Gene Smarte

Whoa, mule, whoa!

—‘Buckin’ Mule,” traditional folk song

Whoa, mule, I say!

I ain’t got time to kiss you now,

The mule has run away.

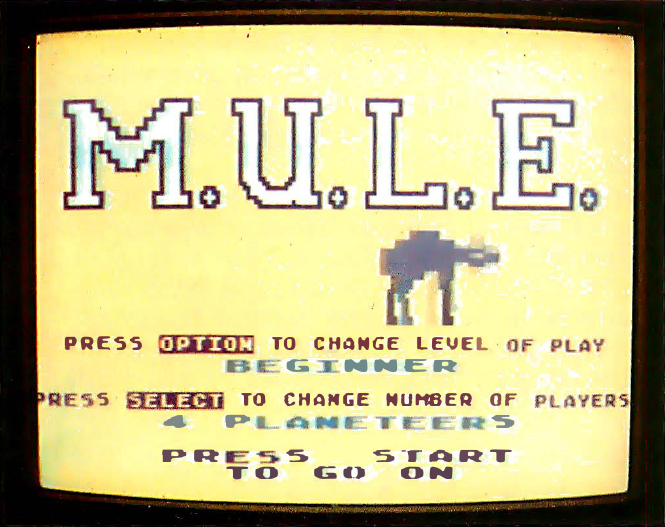

The fun-to-use economic strategy game M.U.L.E. (multiple-use labor element) lets you plot the economic development of a new territory on a planet called Irata. With your grubstake of money and goods and your

knowledge of capitalism, you and three other “planeteers” are ferried to an undeveloped area of the planet. Once there, using the limited supplies of the general store, the planet’s only structure, you must decide how to make the best use of your resources. Your supply ship won’t be back for at least six months.

of planeteers, and decided which of eight characters you’d like to be,

the disk leaves the demo mode and loads the game. You’ll see your

spaceship pass over Irata, descend and deposit you and your fellow

planeteers, and disappear from view.

Before the game begins, the program introduction takes you through a demonstration in which you (and the computer, when there are fewer than four players) select a color and the type of creature—there are eight

kinds—you wish to be. A brief description of each and its advantages and disadvantages is included. The computer always picks the mechanical Mechtron—but so can you. You also select the game level: beginner, standard, or tournament.

As the game begins, you have just landed on Irata and are watching your only link with help, your supply ship, cruise off into space. A status report lists the resources of each planeteer and the general store. (In the tourna-

ment-level game, the planeteers have but one round to become self-sufficient because their supplies are good for only one month.)

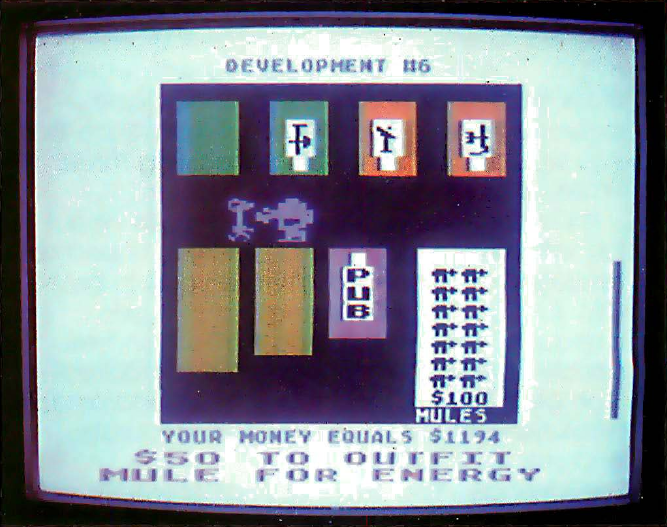

pay your money, outfit a M.U.L.E. for your selected task, and head

out to install the critter. The empty colored rectangles become addi-

tional choices as the difficulty of the game increases. The vertical bar

at the right edge is a shrinking time indicator; when it’s gone, your

time is up.

While “mule” might conjure up images of bearded prospectors and four-legged flop-eared beasts of burden, this M.U.L.E. is actually an intelligent (though sometimes unpredictable—it can run away) machine designed

to resemble a real mule. You purchase it at the general store. Each M.U.L.E. must be outfitted for the task you choose: farming, energy production, or mining. Those are the main tasks of this game.

As in real societies, or “life in the rest of the galaxy,” as mentioned in the player’s guide, a balance must be struck between various needs and wants. In the case of Irata, you must have food, so farming is a requirement;

you must have energy for the creation of all products, so energy production is necessary; and you must mine Smithore, the stuff from which a M.U.L.E. is made (except at the beginner’s level), to ensure availability of

the M.U.L.E. as the scope of Irata’s development increases.

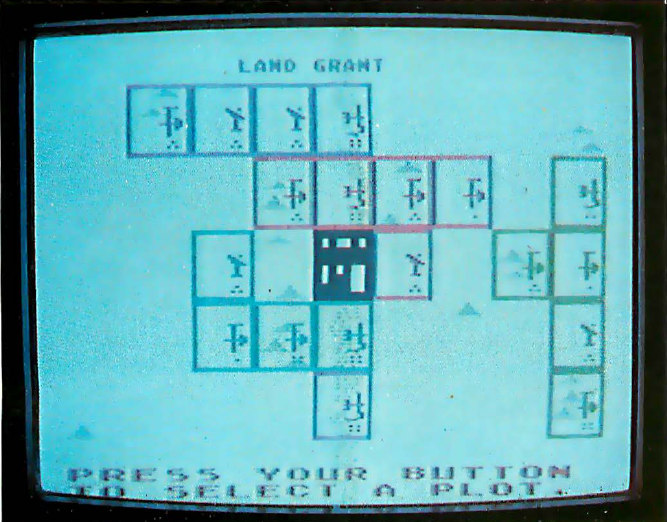

After the resource status report, the display shows an aerial view of the area of Irata to be developed. The landscape includes a fertile river valley ideal for farming, prairies for open-space energy production, and moun-

tains for mining. A cursor scans the territory, and each planeteer chooses a plot of land by pressing a joystick push button. The color-coded plots correspond to the colors the planeteers select earlier in the game.

After the first round of plot selection, each planeteer has a limited time to enter the general store, decide which type of production best suits the plot just selected, outfit a M.U.L.E. accordingly, lead, via the joystick, the

M.U.LL.E. out to the plot, and install him (a M.U.L.E. is referred to in the masculine). Should you have some time left over, you can return to the pub in the general store and do a little gambling or go Wampus hunting.

Gambling is an automatic way to win, but it ends your turn.

ored squares identify players’ plots. Symbols within each square in-

dicate that a M.U.L.E. has been installed. The best food production

is in the central river valley; energy gathering is best in the plains;

the mountains are loaded with Smithore.

The Wampus, as explained in the Player’s Guide, lives in mountain caves, and when he opens his door a light flashes that signals his whereabouts. You must move quickly if you expect to capture him. He’s difficult

to catch, but he’ll pay you to let him go.

When each planeteer has installed a M.U.L.E., production begins automatically. But, just as in real life, random events can help or (more likely) hinder your production. Planetquakes, meteor showers, and an imaginative array of pest attacks can wipe out a turn’s production. These random events are particularly clever in concept and execution and had me looking forward to the next one.

After production, planeteer and store resources are displayed and an auction for each commodity begins. Here, a dog-eat-dog capitalist mentality can help. But you must remember that if, for example, all the planeteers

try to corner the Smithore market and no one does any farming, you all have a good chance of perishing on Irata (shudder). I liked this touch of realism.

If you have the cash, you can buy what you want, and you can sell any surpluses, providing someone is interested. Both buying and selling prices are set by the planeteers with some limits in the beginner’s level. The

program sets the store’s rate of exchange. With the conclusion of the auctions, an updated status report prepares you for the next round of plot selections as your first month of development ends. The game continues

for 6 turns (beginner) or 12 turns (standard and tournament levels). At the conclusion, the player who has accumulated the highest net worth is the winner.

this case, the seller has come down to $32 per unit; the buyers, how-

ever, are unimpressed as they are holding fast below the rock-bottom

bid of $15.

It’s impossible to adequately describe all the interaction and economically realistic subtleties of M.U.L.E. The standard level increases the complexity of the beginner level with land auctions and selling, development-strategy nuances, and gyrating resource prices. You can also sell below a “critical level” if you think that you can make it up later. The tournament level adds Crystite mining and Collusion (private trading between friends).

Tournament play requires some fast thinking and razor-sharp business savvy because the time allowed for decisions is significantly shorter.

M.U.L.E’s packaging and documentation make entertaining reading. In addition to providing an interesting description of the game’s flow, the authors unveil their personal strategies. And the 20-page M.U.L.E. Player’s

Guide is peppered with playing tips along with the economic realities of pricing, economies of scale, the learning-curve theory of production, and the law of diminishing returns. This is definitely not a simplistic,

learn it/be bored with it, kill-the-galactic-villains time-waster.

Conclusion

M.U.L.E. is an intriguing way to illustrate some of the triumphs and perils of free enterprise. While it falls in the broad category of games, it also offers an excellent means to test your business mettle. It’s realistic, too, be-

cause just when you think you’ve done everything right, an unforeseen disaster can happen, like having your M.U.L.E. run away.

Gene Smarte is a BYTE technical editor. He can be reached at POB 372,

Hancock, NH 03449.

At a Glance

Name

M.U.L.E.

Type

Economic strategy game

Manufacturer

Electronic Arts

2755 Campus Dr.

San Mateo, CA 94403

(415) 571-7171

Price

$40

Authors

Dan Bunten, Alan Watson, Jim Rushing, and Bill Bunten

Format

One 5%-inch floppy disk

Language

Assembly language

Computers

Atari 400, 800 with 48K-byte RAM, Commodore 64

Documentation

6-page disk jacket, 20-page M.U.LE. Player’s Guide

Audience

Capitalists, entrepreneurs, and pioneers