Source

- This is a copy of the original article written by Benj Edwards on the PCWorld website, published November 25th 2015. All photos are made by Benj in his family home. Thanks very much Benj for such an excellent contribution to the M.U.L.E. legacy! Personally, I can tell a similar story of M.U.L.E. “bringing family together”, yet with a much sadder note.

- original source last checked working in February 2019

On holidays like Thanksgiving, part of the togetherness (especially with my older brother) has always included video games—especially games for our first computer, the Atari 800.

Released in 1979, Atari intended the 800 (and its junior sibling, the 400) to serve as both advanced follow-ups to its successful Atari 2600 game console and, in the case of the 800, as a competitor to the Apple II. But the Atari 2600 held its ground, remaining commercially relevant until at least 1986, and the Apple II, well, you know.

Think of the Atari 800 as a hybrid between a game console and a personal computer. Advanced custom silicon betrayed its origins as a potent gaming machine. Chief among them were the ANTIC and GTIA graphics chips, which granted the sophisticated sprite controls (among other functions), and the POKEY chip, which could output four audio channels simultaneously for complex (at the time) musical capabilities.

POKEY also managed all player input to the system, allowing up to eight paddles or four joysticks at a time. That made the Atari 800 a very special multiplayer machine.

Of the small number of games that supported using all four controller ports, my brother and I owned and played most of them. In Asteroids, players can blast globby space rocks (or each other) four-at-once. Atari Basketball? Two-on-two on the digital blacktop. And Super Breakout? Oh my: If you hooked four paddle pairs to all of the ports, you could have eight people playing onscreen. It was an absolute blast.

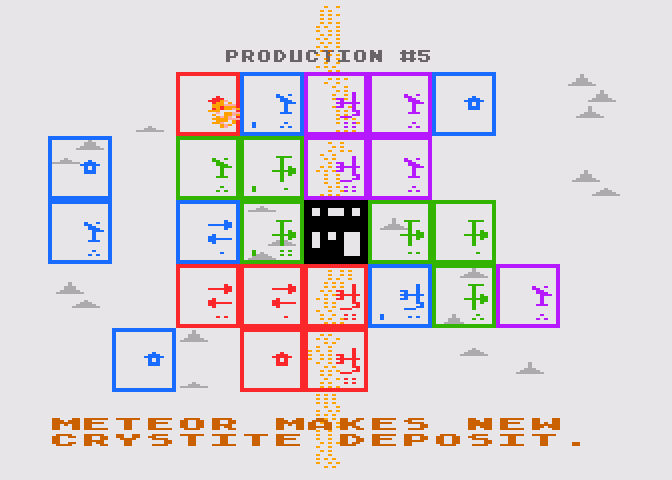

But we must reserve the multiplayer crown for the king of all Atari four-player games: M.U.L.E. Designed by the legendary Dani Bunten and published by Electronic Arts in 1983, this turn-based resource-trading title was never a runaway bestseller, but it quickly became a critically acclaimed computer game. M.U.L.E. combines equal parts depth and dexterity, chiefly from its boardgame-like strategy elements and its four-player, real-time auction sequence. Players move their characters up or down on the screen at the same time to set a buy or sell price. There can be a fair amount of bluffing involved, keeping everyone on their toes.

Boy did my brother love M.U.L.E. One of my earliest memories of the game involves one of his birthday parties. He was probably turning nine, so I would have been four years old—and as eager to be included in whatever the big kids were doing, as they were to keep me out.

On that day, I heard joyous shouting and laughing coming from his room. I pushed open the closed door (as in, “keep out, no little brothers allowed”): The glorious tones of the M.U.L.E. theme song emanated from a color TV propped up on his desk.

My brother and three friends each clutched a black Atari controller, and I watched as he started up a game on the hardest “Tournament” setting. I lurked at the back of the room, mostly unnoticed, as the game engrossed the crowd.

The entire play-through likely lasted only 30-45 minutes of real time, but it felt like a brilliant eternity. In the age of twitch games like Asteroids, where you frequently got blasted away within 30 seconds, 30 minutes was an epic commitment of time and attention span for a kid. The fact that M.U.L.E. kept a room full of nine-year-olds glued to the screen for that long meant it was truly something special.

M.U.L.E. Lives Again

I’ve played M.U.L.E. many times since then. Throughout the 1990s, my brother and I hooked up the 800 every Christmas and played the classics. We still manage it most years to this day.

This year, I decided to pull a Benj and set up M.U.L.E. once again—but at my parents’ house, for the most retro feeling possible.

The centerpiece would be our family’s old woodgrained RCA TV set. Hailing from a time when people built TV sets to look like furniture, it saw non-stop daily service until 2006, when it finally lost out to an HDTV.

I knew it was too important a family artifact to discard, so I tucked it away in the darkest corner of my parents’ garage. I dug out the old, 100-something-pound set and cleaned off all six of its spiderweb-encrusted sides. Then I stuck it in the traditional TV corner in the den at her house and hooked it up.

“What could make this look more ‘80s?” I asked my mom. She brought in a basket of fake flowers, which she set down on an antique children’s chair. Then she placed an old wooden duck on top of the TV, and I found a vintage brass lamp. Instant country-style decor, 1980s-style. My mom’s favorite.

I also rounded up a Betamax player a friend gave me (sadly, our original VHS VCR met the scrap heap long ago), a Zenith cable box that’s just like the one we used back in the day, and an old clock. Finally I hooked up the Atari 800, put in the M.U.L.E. disk, and threw the switch.

My face lit up with joy as I heard the first few beats of the triumphant M.U.L.E. theme song play through the vintage TV set.

To me, history is as close as we can come to time travel. These artifacts are cues that pull up powerful memories. People who say, “don’t live in the past” obviously didn’t own an Atari.

I plugged in four bona-fide Atari controllers and played through a beginner-level game against three computer players because, well, it’s not Thanksgiving yet. My mom had already gone out back to start a bonfire for fun (she does that). Come Thursday, I hope to have four people at the controls, firmly commanding our makeshift time machine.

Happy Thanksgiving, everybody.