We conducted one-on-one interviews with Alan, Bill and Jim respectively, which are amalgamated here. Alan, Bill, Jim – thank you VERY much for taking the time to do this! Although it is hard to find really “new” revelations after 40 years, I hope you enjoy reading the interviews as much as I enjoyed conducting them. It was really great talking to the team! Special thanks go out to Andrew Dieffenbach, who co-authored some of the questions.

Update June 2024: Andrew Dieffenbach, M.U.L.E. Online developer and WoM contributor, succeeded in contacting Roy Glover, M.U.L.E. musician, as well. Though one year late for the “official” 40th anniversary in 2023, nevertheless this is an extremely interesting read, diving back into Roy’s career as a musician and involvement with Ozark Softscape. Head over here for the Roy Glover interview addendum to the 40th Anniversary Special.

WoM: As one of the few 1983 games, M.U.L.E. is never forgotten, and still has active players meeting for cake or barbecue tournament games 40 years after, bringing people together. How does that make you feel? How would you describe the legacy of M.U.L.E.?

Alan: I am pleased people still find fun and pleasure in the game. It was the first multiplayer game that allowed real time simultaneous play (in the auction).

Bill: I believe it helped set the tone for interactive fun while learning without thinking about learning. The sense of fun has grown into many modern games as you see the playfulness in games like Zelda.

Jim: I can’t believe it’s already been 40 years since M.U.L.E. was created – I‘m still in denial! The heart of M.U.L.E. has always been the multiplayer piece, with its strong emphasis on the social aspect of the gaming experience. This core element has played a vital role in its lasting appeal and continued influence in the industry.

WoM: Jim, after Ozark, you were at Electronic Arts for 28 years. How was the M.U.L.E. legacy preserved there?

Jim: I took on a variety of roles such as programmer, producer, and technical director. Towards the end of my time at EA, I joined the Learning & Development department, focusing on helping our teams avoid making the same mistakes repeatedly. In the early to mid-2010s, EA faced challenges adapting to the new online business model, which was replacing the traditional disc-based approach. To help ease this transition, I created a simple hybrid card game and computer simulation, designed to teach the new business model to development teams. Drawing inspiration from the spirit of M.U.L.E., my game was built around the concept of suspension of disbelief. I incorporated random events, the social experience of people sitting together, and KPI dashboards into the game, which featured very simple models. These elements were enough to enable the suspension of disbelief, and the approach proved to be highly effective. I traveled to various EA studios, sharing this innovative learning tool with teams across the company, helping them adapt to the rapidly changing landscape of the gaming industry. The legacy of M.U.L.E. is still present at EA, with conference rooms named after it and a gaming room that has a real Atari 800. There’s also a wall showcasing early EA titles, further demonstrating the lasting impact of M.U.L.E. and its influence on the gaming world.

WoM: Do you play the game with your kids or grandkids? I asked my own kid (5yo) what he likes best about M.U.L.E., and his immediate response was “der Wampus!” 🙂 Any ideas on how to best “pass on the torch” for the game in a broader context? Has it ever been considered to be used in an educational context (teaching basic economics in a fun way)?

Alan: I have two sons who played computer games from very young age (even before they could play M.U.L.E.). While I don’t know whether it’s been used in education, several economic principles were used for production – economy of scale, proximity, time of production, and number of producing units. Even store prices were part of the simulation.

Bill: My grandson is a dedicated gamer since he was very young. We play games, but never have played M.U.L.E. as I haven’t kept the old Atari. It is a great fun game to play with friends. M.U.L.E. has the main focus on fun and interaction with players, like the board games. It consciously had the element of “Learning by Doing” as well. Supply and demand based on need and varying conditions that influence demand. I play more modern games now, but can see the heritage in how music creates mood and tension excitement in games like we tried in M.U.L.E. as well as engaging characters to appeal to the child in all of us.

Jim: When my kid visited me at EA, we used to play the game together in a special area that had the old setup, including a real Atari. My kid enjoyed choosing the green color, loved to let loose M.U.L.E.s, and of course, they were fascinated by the Wampus. It was a great way for us to bond and share some of the magic of the game that I had experienced in my earlier days.

WoM: One of the reasons M.U.L.E. is so well-balanced is due to the extensive playtesting time invested, by involving the Little Rock Atari fan club. Do you remember any nice anecdote from these sessions?

Alan: Long days when we tested. 3 to 5 groups of players once or twice a week for quite a while. More often than not I watched the players from behind the monitor, watching for confusion or difficulty playing. Couple of nuance examples – I don’t remember which, but player or plot color gets lighter or darker when player enters his own plot. Makes action more visible. In our next game, “Seven Cities of Gold”, diagonal speed is adjusted so players move same speed/distance diagonal as vertical or horizontal. No advantage to moving diagonally.

Bill: Certainly loud and frantic games going on in all of the rooms on a Saturday night. Everyone forgot they were testing in excitement of the challenge, and creative cajoling on the auction. By pushing the limits of the game in real fun testing, we believe we caught many errors on unexpected play. All I can say is it was a riotous time, with full on games in each room. Being competitive I was just solely committed to winning in my games and Dan and Jim did more of the monitoring. A lot of the strategy in the cover notes attributed to me came from the testing and finding ways to cajole people in the auction to get an advantage.

Jim: Involving the Little Rock Atari fan club in our playtesting was an excellent way to gather feedback and improve the game. Today, we would call it crowdsourcing, but back then, everyone, especially the club members, was just thrilled to contribute to the game development in that way. We held sessions in the evening after work, sometimes once, sometimes multiple times, in the hall just behind the large window seen in the picture [in chapter 1]. Many gameplay nuances emerged from these sessions. Interestingly, women were also part of the Atari fan club and enjoyed the game a lot. Our team at Ozark would watch the sessions closely to spot bugs and observe player behavior. I remember one particular day when I was quite embarrassed because we had a full house, and someone encountered a bug in my auction code. I felt really down that day, but it pushed me to improve. Dan was the analytical one – he knew everything about the game, and his main focus was on finding and fixing bugs. Dan was truly a real genius, possessing incredible talent in many different areas, including strong engineering skills. His contributions to our projects were invaluable, and his ability to excel in multiple disciplines made him an integral part of the team. His intellect and creativity were truly remarkable, and I feel fortunate to have had the opportunity to work alongside such a talented individual. Bill was great at making connections and coming up with creative solutions. He was very competitive and almost ruthless when playing. The team’s creativity happened organically during sessions in the hall room (directly behind the big front window of the house), and it’s hard to attribute specific ideas to individuals. Bill came up with the idea that M.U.L.E.s could run away, which can actually be a strategy for manipulating the smithore market when timed right. Alan, who worked on both programming and art, had spiral notebooks to create flip-book animations. I believe it was Alan, with his balancing and deal-making personality, who invented the idea that if the colony didn’t survive, no one would win. He wasn’t a fan of the cutthroat aspect. The concept of collusion was added quite late in the development process.

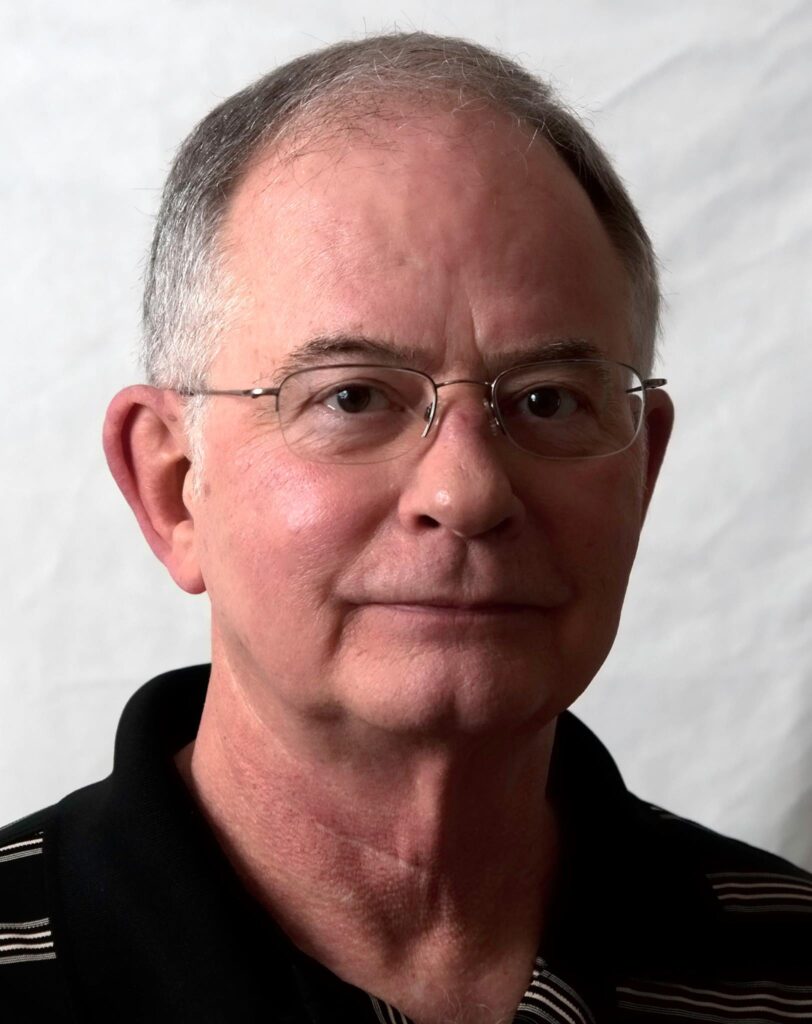

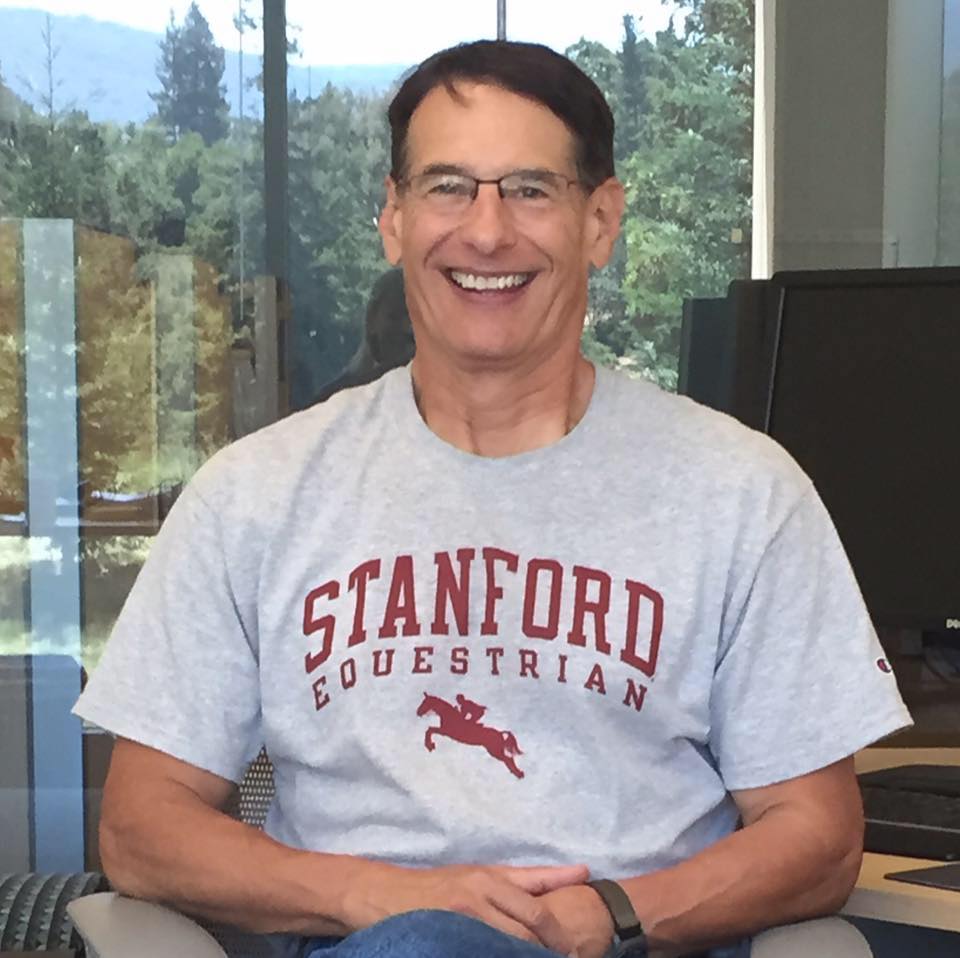

Jim Rushing and World of M.U.L.E. curator Christian Schiller enjoying the interview session, which was held by Zoom and transcribed to text afterwards

WoM: Was development time of M.U.L.E. particularily hard? How were the typical working times? Did you work against tough deadlines, was there a “crunch time” towards the end? How was it compared to later games – easier/better or harder/worse? Biggest obstacle you had to overcome?

Alan: It took 9 months and the end was the hardest. With most of our games, we had to decide what to cut. It was hard to keep it down to 48K. Compile times were long… maybe more than an hour. Only Dan’s machine had 4 disk drives. 2 RAM disks and 2 Apple disks. We all had 2 Apple drives though.

Bill: It was a creative team effort high point for Ozark. The creative design revolved around brainstorming sessions with the rule being no programming judgement. Ideas flowed and in typical mixture of fun and spontaneity. I would record them on flip charts and Dan and Jim would re-look later with their programming hats on. We didn’t have any boundaries from EA at the time, just a business oriented game with graphics and personality. From our side, we wanted to introduce a realtime multi-player aspect that was great with board games but largely missing with computer turn based games. The games foundation start was Cartel and Cutthroats on the Apple II that Dan and I did that incorporated economics in a turn based multiplayer game. It became a bit of a cult game at Apple where Trip Hawkins worked so he wanted us to be part of his launch at EA. He liked the John Dewey philosophy in the game that you learn by doing. Which we expanded in the realtime auction of M.U.L.E.. We did a lot of thinking and discussion on play and playability. We knew key elements included discovery, reward, reinforcement and sense of achievement combined with fun. Pace was important factor, with periods of discovery contrasted with hectic action. The computer graphics and sound were to reflect the different moods along with setting a consistent theme for the game. It helped us forge our links and working practices to go on to other games like Seven Cities of Gold. The hard bit as I remember was the programming by mainly Dan and Jim to fit the creative ideas (or some aspect of them) into machine limitations of the time. Alan did the same with the character animations.

Jim: While the development time of M.U.L.E. wasn’t particularly hard, we faced several challenges due to the limitations of the technology back then. We didn’t have any tools for debugging, and manual merging of code was cumbersome and error-prone, without any recovery options. I recall one session where Alan and I merged our code updates for the C64 build, and all we got was a black screen. It was a humbling experience after putting in so much manual work. We didn’t have any design tools either, so we used graph paper. Getting the auction mechanics right was particularly challenging. Despite these difficulties, we were driven by excitement, and it felt a lot easier than the non-stop work in the later gaming industry. From beginning to end, the development took about nine months. We had a small group, and each member brought a unique perspective. Our team dynamics were characterized by a great fit and mutual respect. Bill was the least technical, but he was good at pulling things together, identifying patterns, merging concepts, and ensuring that we had fun throughout the process. One of the most nerve-wracking aspects of development was dealing with the differences in machine architectures between the Atari and C64 systems.

WoM: Do you remember any significant game feature changes requested by publisher Electronic Arts (e.g. Trip Hawkins or Joe Ybarra or others)?

Alan: Not for M.U.L.E. but Joe helped some on later games.

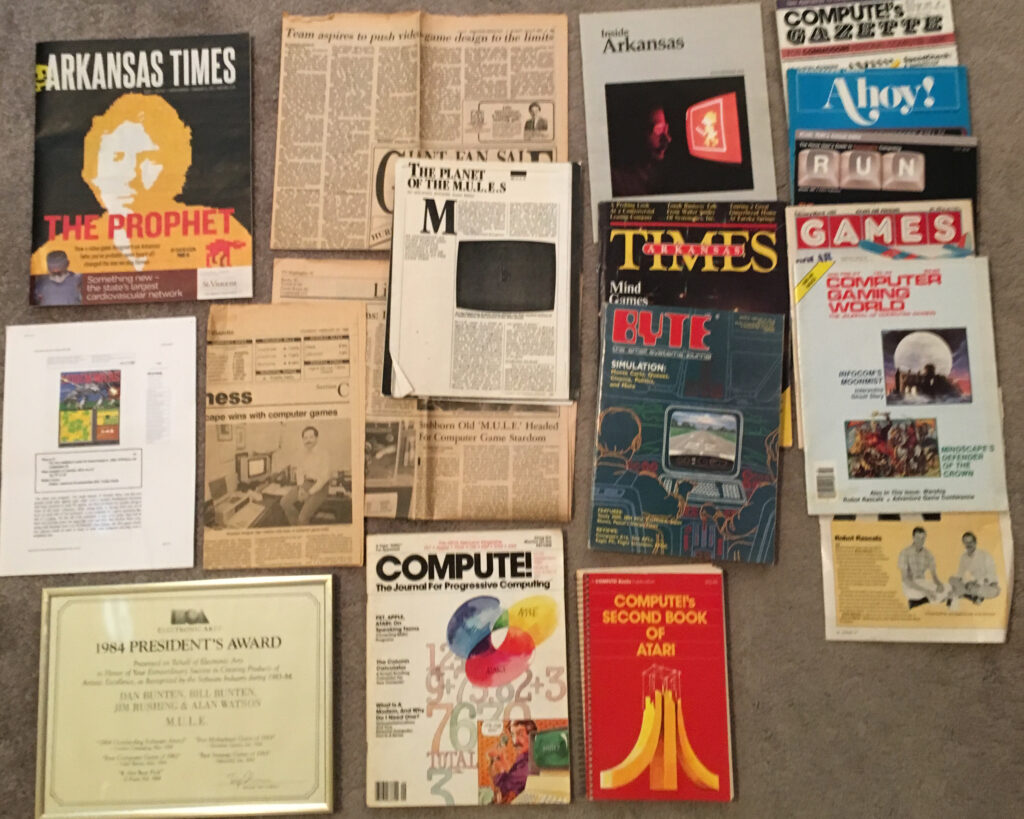

Alan’s collection of M.U.L.E. newspapers

Bill: Trip was very interested in the John Dewey philosophy of learn by doing, so him and Joe really latched on and encourage the interactive auction. Trip and EA were very supportive with the new Computer Game development model being artist drive with producer monitor. Joe even came to our weekend retreat session on a cabin in the Ozark Mountains, so he would contribute and keep EA informed. It was very intense series of Brainstorming sections, with the addition of a neutral member – Joe. It changed the dynamic as Joe could take a big picture view, probing issues like a ‘Neat idea’ vs its ability to fit into the limited memory and impact on schedule. Joe was very supportive but excellent at a broad commercial steering of the project. He was not very good at the volleyball or frisbee fun in between. We also could make him apprehensive with exaggerated stories on our wildlife in the Ozarks where we rented cabins for the retreat, such as wolverines (never seen) and copperhead snakes (rarely seen).

The wampus, a late addition to the game, is inspired not by the game Catch the Wumpus, but by the local legend of the six-legged wampus cat, which is also the mascot of the Conway football team, near where Dan lived. Bill can’t remember for sure, but thinks it was probably Dan’s love of the outdoors.

Jim: I recall that Joe Ybarra, our producer from Electronic Arts, visited us a few times and would always bring new ideas with him. However, EA was quite respectful of our creative process and never forced any significant game feature changes on us that we didn’t want to implement. The collaboration was quite harmonious, and they allowed the Ozark team to maintain our vision for the game.

WoM: I have read that the Ozark team would sometimes play football out in the lawn. Was the Auction screen’s interface designed after football? Perhaps subconsciously, if not? Any other sports games or board games which may have inspired elements of M.U.L.E. based on the team’s experiences? Any other “Ozark team anecdotes” to share?

Bill: Lots of games were played along with development including football, computer games and board games. The intent was to keep competitive bonding and creative juices flowing. The basic idea came from Trip Hawkins who as founding influence on Electronic Arts wanted a game in the original release portfolio that would be an extension of Cartels and Cutthroats. That game was a development of Dan and mine on the Apple published by SSI. A strategic line of games that Dan has already published Computer Quarterback with that concentrated on business resource decisions with different playing styles that could influence the game at key points. It apparently was a bit of a cult hit within Apple where Trip worked as Director of Marketing for the new Lisa computer at the time. Trip had a philosophy based on John Dewey that we learn best by doing. The idea was extended into more graphic available hardware that was becoming available and more emphasis on creative fun and less on business decisions. A couple key concepts early were more fun bus still learning economics of demand and supply and more player interaction or in Trip and John Dewey’s words “by doing” The auction was a result of simulating the real world on commodity movements and also to move away from player based turns and have the fun of live action with the ability to yell, persuade, threaten your opponents as part of the strategy.

WoM: Did you contribute to any of the turn events (Mischievous glac-elves, Two-legged kazinga races, etc.? Who else or did write them? Any inspiration or story of their creation?

Alan: Random events between rounds took the place of “Go to Jail” [WoM: A message which can still be found, unused, in the game]. We all worked on those. We wanted to distribute events for all species. Used to help people who were behind (subtlety). The Wampus was an after thought. We had pretty much finished the game when it was added. Kind of helped player who fell behind.

Bill: The game development was an iterative process of general guidance by Dan or Joe, and then real brainstorming with as much fun and creative as possible. All was done on Flip Charts which I did with the rule being no judgment. The next stage was scrutiny for what would work and trade offs on computer memory and space. Everyone contributed as part of the Story Board brainstorming but would say Alan as more cartoon animator was most at home with the characters.

WoM: Were you (i.e. the whole Ozark team) involved in developing the C64 port, or was it done by other people (or Ozark plus additional people from EA – I heard a rumor Rebecca Heineman was involved)?

Alan: Just Ozark for the C64 port. No outside help with the port.

Bill: Dan, Alan and Jim were involved in the programming and porting and would have been aware of any outside help.

Jim: The C64 port was primarily developed by Alan and me, while Dan had already moved on to the design of our next game. Heinemann wasn’t directly involved in the C64 port, but it’s possible that he may have had discussions with Dan, who had a larger network and was more connected with the folks at EA. Overall, though, the bulk of the work on the C64 port was handled by Alan and me within the Ozark team.

WoM: What was the development timeframe for the C64 version, and was it easier or harder than Atari?

Alan: I don’t remember the total time for C64. We had to learn a different computer – including ways to uncover more RAM. I don’t remember any intentional changes for C64 except those that had to do with machine differences. Background movement easier with Atari (display list interrupt). Colors and sizes probably due to differences between players on Atari and sprites on C64.

Bill: Yes, I remember the discussions of the Atari built in graphics lending help to the programming and the C64 was a battle with them to port.

Jim: The development timeframe for the C64 version was about two to three months after we finished and shipped the Atari version. In terms of difficulty, the C64 was actually harder to work with. The interrupt handling was more complex, and I still remember the importance of $D012 to this day. The Atari’s machine architecture was much cleaner, which made the C64 more challenging and less enjoyable to work with. We had implemented so many tricks on the Atari, and transferring them to the C64 proved to be a demanding task. Additionally, the lack of joystick ports on the C64 and having to design a keyboard interface was something we weren’t particularly fond of.

WoM: How did your development chain look like? You cross-compiled Atari and C64 code on an Apple II, actually pretty advanced for that time?

Jim: Our development chain for M.U.L.E. was relatively simple by today’s standards. The design process had already started with Dan during our time at SSI. We used the SC Assembler, which was a great 6502 assembler developed by a guy in Texas. To transfer code between the Apple and Atari & C64 systems, we used a serial connection to avoid the need for floppy disk transfers. To speed up the compiling process, we employed RAM disks on the Apple II, which allowed us to bypass the slower floppy disks. This setup helped us streamline the development process as much as possible, given the technology available at the time.

WoM: To our knowledge, Atari M.U.L.E. was in stores May 23rd 1983, considered it’s birthday. Do you know when the C64 version hit stores, and how the sales figures split between Atari and C64 (how many copies sold for which platform)?

Alan: I don’t remember release dates for either product.. Sales were disappointing with piracy estimating as many as 10 copies for every one sold. I don’t remember stats concerning sale numbers.

Bill: The C64 Port was complete in Nov 83. I don’t have games selling figures anymore.

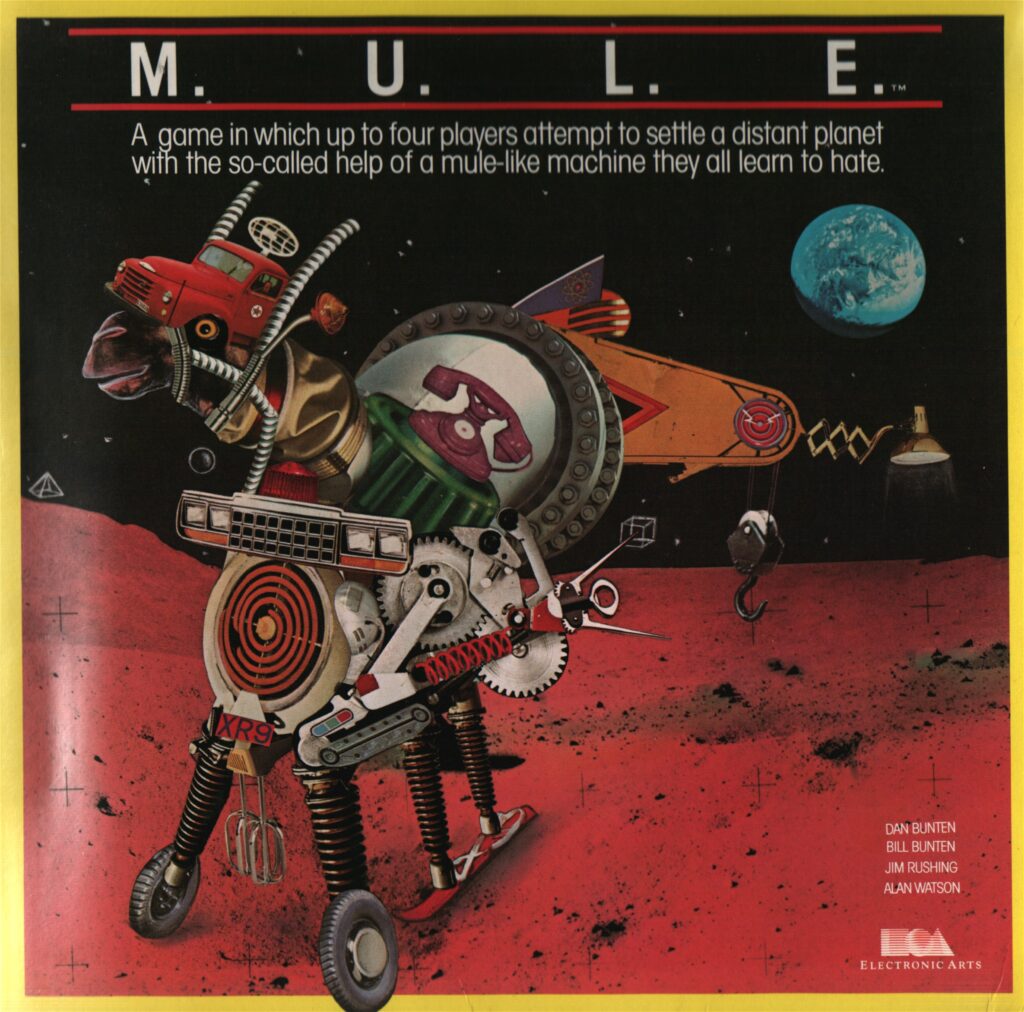

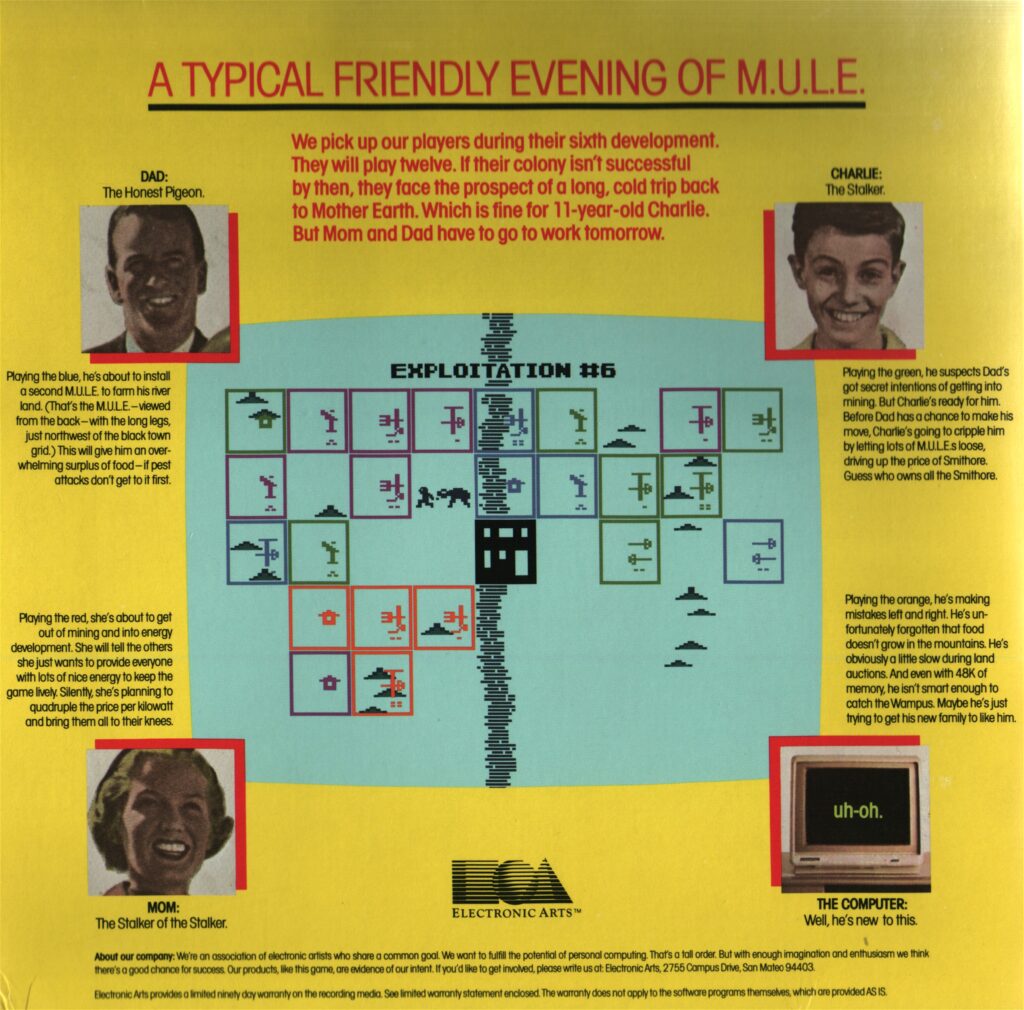

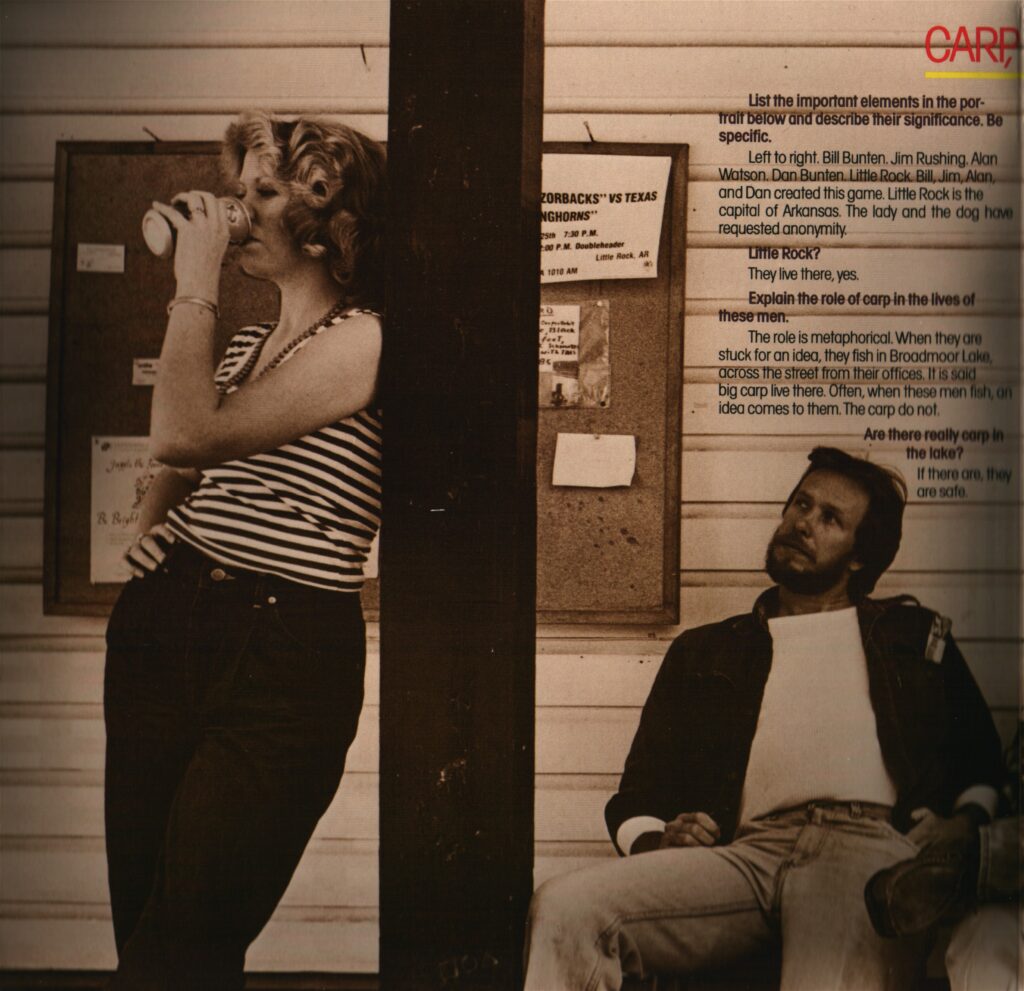

Jim: The sales of the C64 version of the game significantly eclipsed those of the Atari version, primarily due to the larger installed computer base for the C64. It’s interesting to note that all the artistic marketing for the game was done by EA, and we didn’t see the cover until very late before publishing. When we finally saw it, we all thought it was quite weird! However, we absolutely loved what EA did with the back cover, as it captured the spirit of the game and the social aspect very well. It was a great representation of the experience we aimed to deliver to the players.

The woman is Bunten’s sister Terri – which explains why her brother Bill was a bit uncomfortable looking at her for the photo. The photo was taken in “Hillbilly Country” in the Little Rock hinterland, the scene was created by EA’s PR agency Goodby – only the dog was spontaneous, he belonged to the General Store in front of which the photo was taken. Bill has a “Slick Willy” in his shirt, a typical Arkansas beef jerky.

WoM: After release, how many M.U.L.E. skinner awards did you sign, and during which timeframe? ( Do you still have some blank ones left so that the World of M.U.L.E. could start continuing this tradition? 🙂 )

Alan: Ha ha. I forgot about M.U.L.E. Skinner awards. You would have to check with Dani’s daughter or whoever has rights to the game to find out more.

Bill: I think about 100 if memory serves.

WoM: Were you involved in any of the other ports of original M.U.L.E. to other platforms (IBM PCjr by K-Byte Software; Japan releases by Bullet Proof Software: MSX, PC-88, Sharp X1)? If so, any anecdotes/stories to share from this experience? Any info available on how well they sold? Do you have a personal favourite of these other ports?

Alan: No. Only original and C64. All others missed so many details they were very poor substitutes.

Bill: I don’t know for sure if the team was involved other than overview.

Jim: After the Atari and C64 releases, EA was eager to get the game out to as many other platforms as possible. However, due to the different architectures of those platforms and our focus shifting to Seven Cities of Gold, we couldn’t work on those ports as quickly as EA wanted, and we weren’t heavily involved in them. Later on, we did take a look at the final results for some of the other ports, such as the Pcjr version. To be honest, we were quite depressed because the quality was so disappointing compared to the original Atari and C64 versions.

WoM: The Nintendo NES port from 1990 – 7 years later – can be considered to be the first “remake” of the game. Have you been involved with this? If so, any anecdotes/stories to share from this experience? Any info available on how well it sold?

Alan: No involvement. I saw it once or twice and was not happy with it.

WoM: Were you involved in any of the (sadly failed) porting attempts (Atari ST, Amiga, Sega Genesis) or sequel attempts (Son of M.U.L.E. for Sega Genesis; Online Planet Pioneers?)? Any anecdotes/stories to share from this experience?

Alan: My work for Dani was to design more characters and their animation.

Jim: During the early ’90s, when Dan – in the midst of transition to Dani – was back at EA working on those porting and sequel projects, I wasn’t directly involved. However, we did meet up for beers a few times and discussed the projects. From our conversations, it seemed that EA was putting a lot of directional input into the projects, and some of their suggestions, like adding “guns and bombs,” didn’t sit well with us. As time went on, the enthusiasm for making a remake shifted to a different sentiment. We started to feel that some things, like the original M.U.L.E., are best left as they are and shouldn’t be tarnished if you can’t completely control the design. In the end, that’s what happened with those porting and sequel attempts.

WoM: Did you play any of the modern remakes of M.U.L.E. (Planet M.U.L.E. online, or the Board Game from Finnish publisher Lautapelit), and if so how did you like them? What is your favourite version of the original game – Atari or C64?

Bill: Atari. The joystick mainly (and quicker load times) worked better for me with the Atari as I was very hard on joysticks.

WoM: If you had just one wish for the future of the M.U.L.E. legacy, what would it be?

Alan: I don’t know how to top M.U.L.E. without making an overly complicated game. Part of it’s appeal is it’ simplicity. Every sequel and every port I saw missed the subtley and nuance of the original.

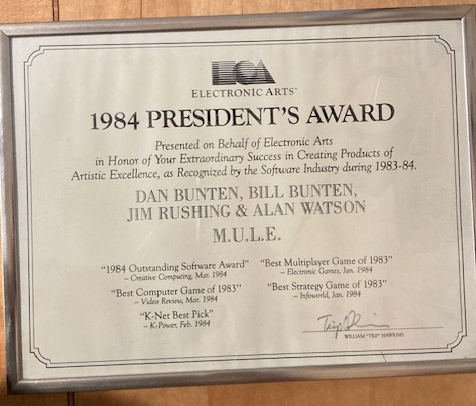

EA president Trip Hawkins’ award to the Ozark team for “Artistic Excellence” of M.U.L.E. – photo courtesy of Alan Watson

Bill: That Game designers continue to push the boundaries of what a computer can do and are allowed non corporate creativity to design outside of the box of small iterative improvements to previous games. Games stir friendship, passion and creativity in playing – something we need in fast paced world.

WoM: Thanks very much for the time talking with us. All the best!

With Alan, we took a little more time to deep dive into some of the art design elements:

WoM: Humanoid looks a lot like the main character from Gold Mine. That character resembles the players in Football for the Atari 2600. Was there any inspiration from those games? The humanoid looks like it’s smiling. Was this intentional or was it something else?

Alan: I doubt it was intentional. Gold Mine was my first video game so I sure the human was influenced by the figure.

WoM: Do you remember any additional species or variations that were intended to be in the game? If you were to design new species today, what would you create?

Alan: That’s what I was doing for Dani in the 1990ies. I don’t remember them however. I’d have to think about new characters. I think Dan gave me very specific pixel sizes. Now, that limit would be very different. The animation would be much smoother.

WoM: Back to Atari Football. It resembles the Auction screen. I read that the team was very interested in American football. Was the Auction screen modelled after football?

Alan: No football influence Dan had done a game, Cartels and Cut throats. The auction was a major refinement improvement. We needed realtime 4 player graphic to show bids sale prices, store price. Started left to right but chose vertical to more easily show relative amounts.